FMCSA's Non-Domiciled CDL Saga and What the AFSCME/AFT Lawsuit Actually Means for Trucking

A teachers union, two truck drivers, and the future of commercial licensing walk into federal court. This isn't a joke. (Follow-up from my 10/21 Article on the original filing of this petition.)

On September 29th, the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration did something long overdue and they shut down a non-domiciled CDL issuance process that had become a regulatory disaster.

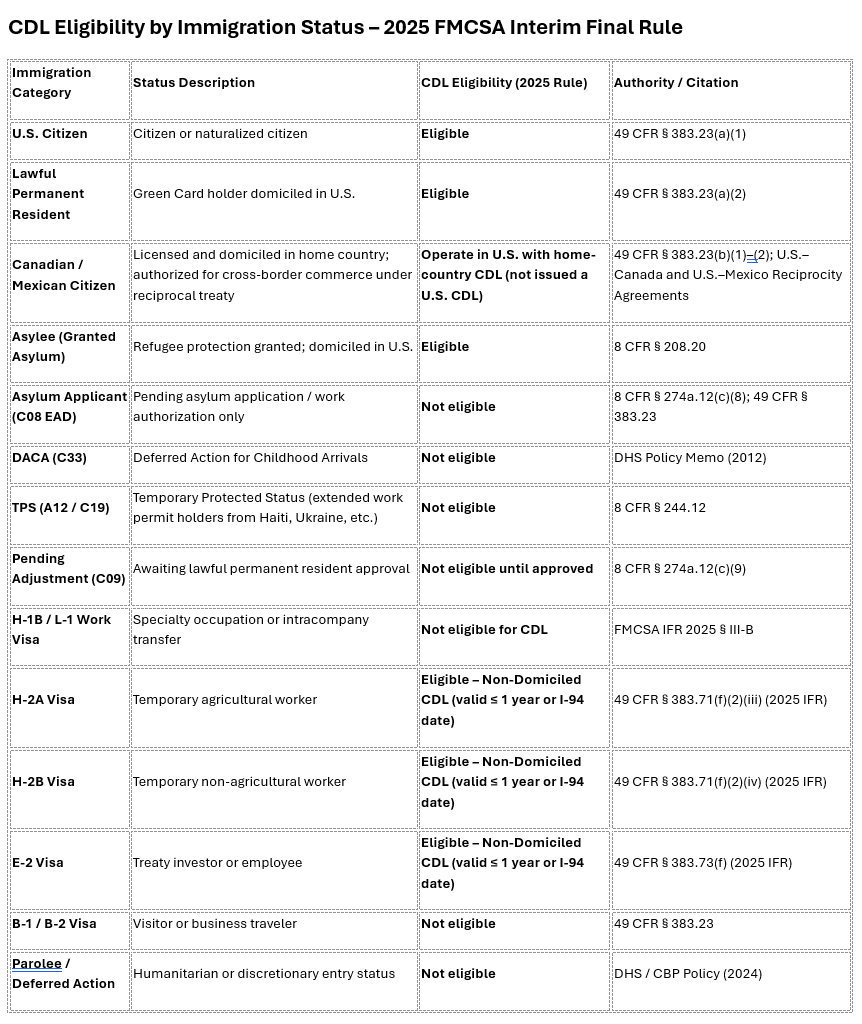

The interim final rule, effective immediately, limits non-domiciled CDL eligibility to three specific visa categories: H-2A (temporary agricultural workers), H-2B (temporary non-agricultural workers), and E-2 (treaty investors). Everyone else who was getting non-domiciled CDLs under the previous framework, asylum seekers, asylum applicants, refugees, DACA recipients, TPS holders, is no longer eligible.

My cheat sheet for fleets on what this means is here:

This wasn’t arbitrary. This was necessary.

FMCSA’s 2025 Annual Program Reviews uncovered systemic failures across multiple states in how non-domiciled CDLs were being issued. California alone had a 25% error rate, one in four non-domiciled CDLs issued improperly. Colorado, Pennsylvania, South Dakota, Texas, and Washington all had similar problems.

States were issuing CDLs with expiration dates extending years beyond the holder’s work authorization. States were issuing non-domiciled CDLs to Mexican nationals who shouldn’t have qualified because Mexico has reciprocity. States had inadequate staff training, broken computer systems, and virtually no quality control.

And people died because of it.

The Body Count Justifies Emergency Action

FMCSA identified five fatal crashes in just the first eight months of 2025 involving drivers with non-domiciled CDLs. Let’s talk about those crashes, because they’re not abstract statistics, they’re dead Americans.

August 12, 2025 - Florida Turnpike, St. Lucie County A driver with a non-domiciled CDL who had been living in the U.S. illegally since 2018 after unlawfully crossing the border from Mexico attempted an illegal U-turn on the Florida Turnpike. His tractor-trailer crossed directly into the path of a minivan, which crashed into the truck and became lodged underneath. Three people died. The dashcam video was broadcast nationwide, a minivan full of people obliterated because someone who shouldn’t have been driving a commercial vehicle was given a CDL anyway.

FMCSA’s post-crash investigation found the driver was not proficient in the English language. He’d been cited for speeding in New Mexico previously. He’d only been issued a non-domiciled CDL in California after Washington State improperly issued him a standard CDL in 2023.

This is what happens when state licensing agencies can’t follow basic procedures.

July 11, 2025 - Delaware Memorial Bridge A truck tractor traveling from New Jersey into Delaware crossed three lanes of traffic and crashed through a concrete barrier wall, careening into the Delaware River. The driver was killed. The emergency response required a crane, a barge repositioned from an active construction site, state police dive teams, and fire companies.

The driver had entered the United States unlawfully, was in removal proceedings, and had a valid USCIS-issued Employment Authorization Document that allowed him to get a non-domiciled CDL. He’s dead now, but he could have taken out dozens of other motorists on that bridge before his truck went into the river.

May 6, 2025 - Thomasville, Alabama A tractor-trailer hit four vehicles from behind as they were stopped at a red light. Two people died. Four more were injured. The driver had held his non-domiciled CDL for less than six weeks. FMCSA’s ongoing investigation revealed he initially failed his CDL skills test for speeding and failing to obey a traffic control device, then passed a few days later.

The crash occurred on his third day of employment with the carrier.

This driver wouldn’t have been eligible for a CDL under FMCSA’s new rule, he had an EAD but no I-94 showing one of the specified employment-based visa categories. He got a license anyway, and two people are dead.

March 14, 2025 - Austin, Texas An 18-wheeler failed to brake and crashed into a long line of stopped traffic on I-35. Seventeen vehicles were involved. Five people died, including two children. Eleven more were hospitalized. The crash scene extended for a tenth of a mile.

Texas improperly issued the driver a standard CDL despite only qualifying for a non-domiciled CDL. Post-crash investigation found he didn’t have a current medical certificate and had violated hours-of-service rules multiple times in the 11 days before the crash. His driving record showed two prior citations for failure to obey traffic control devices and erratic lane changes.

January 19, 2025 - Interstate 68, West Virginia. A tractor-trailer driver with a non-domiciled CDL and two prior speeding citations caused a collision on a bridge over Cheat Lake. A vehicle fell from the bridge into the lake. One person died. Investigators determined the driver was traveling at an unsafe speed. He’d entered the U.S. unlawfully, was in removal proceedings, and had a valid USCIS EAD.

He was arrested in California, extradited to West Virginia, and charged with negligent homicide.

That’s 12 dead Americans in eight months. Two of them were children.

Did FMCSA have “good cause” to act immediately, or should they have spent 60-90 days on a notice-and-comment process while more people died?

The Teachers Union That Wants to Preserve This Mess

On October 24th, the American Federation of Teachers and the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees filed an emergency motion asking federal judges to halt FMCSA’s rule.

They argue that the FMCSA acted arbitrarily, failed to prove immigration status connects to safety risk, and didn’t follow proper administrative procedures by skipping notice-and-comment rulemaking.

Why is a teachers union fighting this hard to preserve non-domiciled CDL eligibility for asylum seekers and illegal immigrants?

AFSCME represents 1.4 million public sector employees. AFT represents 1.8 million members, including 13,500 transportation workers. According to their court filing, they’re concerned that school bus drivers, municipal workers, and public transit operators may lose their CDLs.

Let’s be very clear about what this lawsuit is actually about: public sector unions don’t want to lose cheap labor for jobs that should be going to American citizens and lawful permanent residents.

School districts are facing bus driver shortages because they refuse to pay competitive wages. Rather than raise compensation to attract qualified American drivers, they’ve become dependent on a pipeline of foreign workers holding non-domiciled CDLs based on temporary work authorizations that were never intended to create permanent driving privileges.

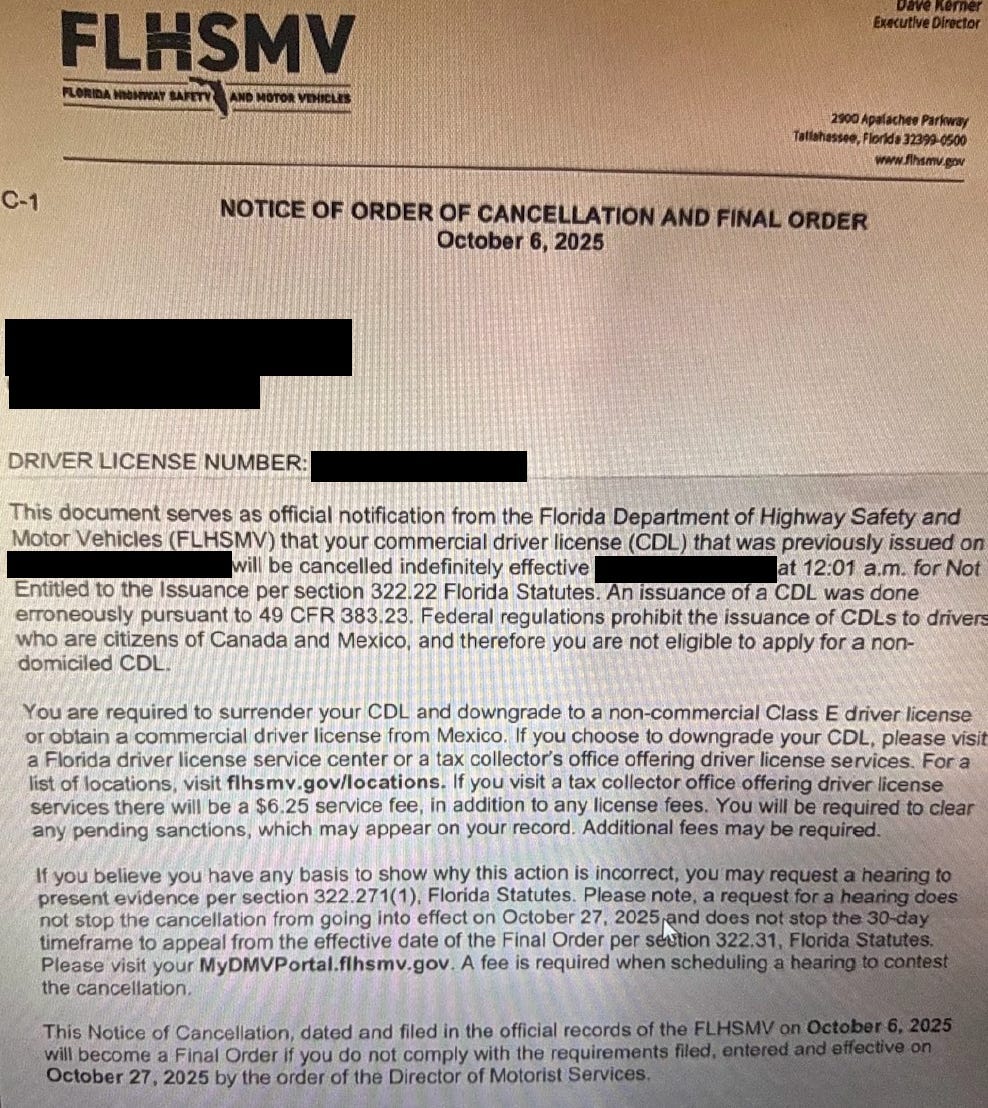

The lawsuit explicitly highlights one AFSCME member who works for the Mercer Island, Washington, Department of Public Works. He’s been employed for 16 years, operating dump trucks, street sweepers, and snowplows. He holds Temporary Protected Status, has a pending green card application, and just had his CDL suspended.

Why hasn’t his green card application been processed in 16 years? Why is he still on TPS after nearly two decades? And why should a municipal public works position, a government job paid for by American taxpayers, go to someone who still hasn’t achieved lawful permanent resident status after 16 years in the country?

What the Statute Actually Says (And Why Non-Domiciled CDLs Are Legally Questionable)

The Commercial Motor Vehicle Safety Act (49 U.S.C. § 31311(a)(1)) is very clear: states must issue CDLs only to individuals “domiciled in the State.”

There’s one statutory exception under 49 U.S.C. § 31311(a)(12)(B): states may issue non-domiciled CDLs to individuals domiciled in foreign countries where FMCSA has determined licensing standards are comparable (i.e., Canada and Mexico) or to individuals domiciled in states with decertified CDL programs.

That’s it. That’s the statute.

When the FMCSA created the 2011 rule allowing non-domiciled CDLs for other foreign nationals based on EADs or I-94 documents, it was expanding beyond the statutory framework. The statute doesn’t authorize CDL issuance to foreign nationals who are temporarily present in the U.S. on work permits, asylum applications, or deferred action programs.

The plaintiffs’ lawsuit argues that FMCSA acted arbitrarily by restricting non-domiciled CDL eligibility. But the real question is: did FMCSA ever have statutory authority to create non-domiciled CDLs for these categories in the first place?

If Congress wanted to authorize CDL issuance to asylum seekers, refugees, DACA recipients, and TPS holders, it could have amended the statute. They didn’t.

The “No Evidence” Argument Is Dishonest

The lawsuit claims FMCSA has “no evidence” connecting immigration status to crash risk. They quote FMCSA’s own regulatory analysis: “There is not sufficient evidence… to reliably demonstrate a measurable empirical relationship between the nation of domicile for a CDL driver and safety outcomes.”

This is cherry-picking to the point of dishonesty.

First, FMCSA doesn’t need to prove a statistically significant correlation across the entire population of non-domiciled CDL holders to justify restricting eligibility. They need to show that the lack of verification and oversight in the current system creates unacceptable risk. They did that, California’s 25% error rate proves the system is broken.

Second, the absence of comprehensive data is itself evidence of the problem. States can’t verify foreign driving records. They can’t track whether non-domiciled CDL holders maintain lawful status. They can’t enforce English language proficiency requirements effectively. They’re issuing credentials to people whose entire driving history is unknown, and then those people are operating 80,000-pound vehicles on American highways.

Third, the five fatal crashes aren’t proof of statistical correlation, they’re proof of systemic vulnerability. Each crash involved a driver who either:

Shouldn’t have been eligible for a CDL under existing rules but got one anyway (Texas, Washington)

Was eligible under the old framework but lacked a verifiable safety history (Florida, Delaware, Alabama, West Virginia)

Had indicators of unsafe operation that weren’t caught during licensing or weren’t acted upon (speeding citations, failed initial CDL test, hours-of-service violations, no current medical certificate)

When your licensing system allows someone who failed their CDL skills test for speeding to try again a few days later, pass, and then three days into their first trucking job, kill two people in a rear-end collision... You don’t need a peer-reviewed statistical study to know there’s a problem.

The English Language Proficiency Problem Nobody Wants to Discuss

Federal regulations at 49 CFR 383.133 require CDL applicants to demonstrate the knowledge and skills necessary to operate a commercial vehicle safely. That includes understanding traffic signs, comprehending instructions, and communicating effectively.

FMCSA’s post-crash investigation of the August 12, 2025, Florida crash found the driver “was not proficient in the English language.”

This isn’t an isolated incident. The driver in the Texas crash had violations for failure to obey traffic control devices. The driver in the Alabama crash failed his initial skills test for the same reason. The driver in the West Virginia crash was cited twice for speeding.

Here’s what the lawsuit doesn’t address: How did these drivers pass their CDL tests?

Many states offer translated CDL written exams in multiple languages. That’s fine for testing knowledge of traffic rules. But it doesn’t test whether the driver can read English road signs in real time while operating a commercial vehicle at highway speeds.

Some states have inadequate standards for evaluating verbal communication during skills tests. Drivers can get through the test with minimal English proficiency, then get on the road and can’t understand dispatch instructions, can’t communicate with law enforcement during inspections, and can’t read warning signs.

When FMCSA restricted non-domiciled CDL eligibility to H-2A, H-2B, and E-2 visa holders, they weren’t being arbitrary. These visa categories require:

Labor certification through the Department of Labor (H-2A, H-2B)

Specific employment tied to the visa (all three categories)

Employer attestation of qualifications, including language proficiency requirements in the job order

An H-2B employer seeking to hire a truck driver must list job qualifications in their DOL application. Those typically include: possession of a U.S. CDL or foreign equivalent, 12-24 months of related work experience, a clean driving record, the ability to pass drug and medical testing, and knowledge or proficiency in English.

The employer has strong incentives to verify these qualifications before going through the 90-day DOL application process, because if the worker doesn’t work out, the employer has to start over with a new 75-90 day application window.

Compare that to asylum seekers with Category C08 EADs. Those EADs are issued to individuals whose asylum applications have been pending for 365+ days through no fault of their own. The EAD proves work authorization, nothing more. It doesn’t prove:

Lawful entry to the United States

English language proficiency

Any specific job skills or qualifications

Verifiable employment history

Clean driving record in the home country

Yet under the old framework, a C08 EAD was sufficient to get a non-domiciled CDL. No employer screening. No job-specific qualifications. No language proficiency verification beyond whatever the state DMV required (which, as we’ve seen, isn’t much).

The “Good Cause” Exception Was Properly Invoked

The lawsuit argues FMCSA violated the Administrative Procedure Act by issuing this rule without notice-and-comment rulemaking. They claim the “good cause” exception doesn’t apply because:

Five crashes aren’t enough to prove an emergency

State licensing failures don’t justify nationwide restrictions

Advance notice wouldn’t actually cause problems

All three arguments are wrong.

On the Emergency:

Five fatal crashes in eight months, 12 dead Americans, and the discovery that 25% of California’s non-domiciled CDLs were issued improperly absolutely constitute an emergency requiring immediate action.

The lawsuit seeks to minimize this by noting that there were over 6,000 large-truck and bus fatal crashes in 2022 (the most recent year with published FMCSA data). Their argument: five crashes are “less than 0.1 percent” of total crashes; therefore, it’s not statistically significant.

This is morally bankrupt reasoning.

First, we don’t know the total number of crashes involving non-domiciled CDL holders in 2025 because the year isn’t over and crash data takes time to compile. We know about these five because they were high-profile, resulted in multiple fatalities, and triggered post-crash investigations that revealed the driver’s immigration status.

Second, any preventable fatalities caused by systemic regulatory failure justify emergency action. If 12 people died because states were improperly issuing CDLs in violation of federal standards, the appropriate response isn’t “well, that’s only 0.1% of total crashes, so let’s take 90 days for public comment.” The appropriate response is to stop the improper issuance immediately.

Third, the crashes demonstrate system vulnerability, not just individual driver error. Multiple crashes involved drivers who:

Were improperly issued CDLs by state agencies

Had prior citations that should have raised red flags

Lacked English proficiency despite passing CDL tests

Had no verifiable driving history from their home countries

The emergency isn’t “five crashes.” The emergency is discovering that state licensing agencies fundamentally can’t implement the existing non-domiciled CDL framework properly, and people are dying as a result.

On State Failures and National Restrictions:

The lawsuit argues that California’s licensing problems don’t justify restricting eligibility in all 50 states.

Wrong.

When FMCSA’s APRs uncovered systemic problems in six states (California, Colorado, Pennsylvania, South Dakota, Texas, Washington) within a single review cycle, that’s evidence of nationwide compliance failure.

More importantly, the non-domiciled CDL framework itself is the problem, not just state implementation. Here’s why:

Non-domiciled CDL holders can drive anywhere in the U.S. A driver with a California non-domiciled CDL can operate in Pennsylvania, Texas, Florida, or any other state. State-specific remedies don’t work when the credential is nationally portable.

States lack authority to verify immigration status effectively. DMV employees aren’t immigration officers. They rely on documents (EADs, I-94s, passports) that they have limited ability to verify. Even with SAVE access, they’re making determinations about immigration law compliance that exceed their expertise and authority.

States have no way to verify foreign driving records. An asylum seeker from Venezuela might have a terrible driving record in Venezuela. A DACA recipient might have entered the U.S. as a child but their parent had a history of violations in Mexico. States have no systematic way to access this information.

States can’t effectively enforce English language requirements. Translated written exams test knowledge, not communication ability. Skills tests conducted by examiners who don’t speak the applicant’s native language may not catch language deficiencies that create safety hazards.

The solution isn’t “fix California’s CDL program.” The solution is to restrict non-domiciled CDL eligibility to categories where federal agencies have already done the vetting.

On the Application Surge:

FMCSA argued that publishing a proposed rule would create a foreseeable surge in applications as people rushed to get non-domiciled CDLs before the restrictions took effect. The lawsuit claims this is speculative.

It’s not speculative, it’s basic economics and human behavior.

When the FMCSA announced the compliance date for entry-level driver training requirements (February 7, 2022), CDL issuances spiked dramatically in the months leading up to the deadline. CDLIS data shows that December 2021-February 2022 issuances were roughly double those of the same period in the previous year.

The lawsuit argues this proves the opposite, that even with advance notice, states handled the surge. But they’re missing the point:

The problem isn’t whether states could process applications. The problem is that states with 25% error rates would process even more applications incorrectly.

If California issues 3,820 non-domiciled CDLs and CLPs per month with a 25% error rate, that’s roughly 955 improper credentials per month. Now imagine FMCSA publishes a proposed rule saying, “We’re going to restrict eligibility in 60 days.” What happens?

Asylum seekers, DACA recipients, TPS holders, and others who would be excluded under the new rule flood state DMVs to get licensed before the cutoff

Applications concentrate in states with known weak enforcement (because word spreads fast, everyone knows which DMVs are “easy”)

States already struggling with 25% error rates get overwhelmed

Error rates go up, not down

Thousands of additional improper CDLs get issued during the comment period

FMCSA’s decision to make the rule effective immediately prevented this exact scenario. Rather than creating a 60-90 day window during which vulnerable systems were flooded with applications, they shut down improper issuance immediately. They required states to fix their systems before resuming non-domiciled CDL issuance.

That’s not arbitrary, that’s the only rational way to handle a systemic compliance failure.

What the Lawsuit Gets Right (But Misinterprets)

The plaintiffs do identify some real problems, but they just draw the wrong conclusions.

They’re Right: Individual Drivers Are Harmed

Jorge Rivera Lujan has lived in the U.S. since age two. He’s held a CDL for 11 years. His entire driving history is domestic. He’s built a legitimate trucking business (Rivera Bros Transportation LLC). His non-domiciled CDL expires November 29, 2025, and Utah DMV told him he can’t renew it.

That’s a real person facing real economic harm.

Aleksei Semenovskii fled persecution in Russia. He has a pending asylum application and valid work authorization. He’s held a non-domiciled CDL since 2020 with zero violations. He started his own trucking company. If his CDL is revoked, he faces loan defaults and loss of his family’s health insurance.

That’s a real person facing real economic harm.

The Mercer Island municipal worker who operates dump trucks, street sweepers, and snowplows has worked for the city for 16 years. He has TPS, a pending green card application, and a spotless driving record. His CDL was suspended in October 2025. He might lose his job.

That’s a real person facing real economic harm.

But here’s where the lawsuit gets it wrong: individual hardship doesn’t override the government’s obligation to enforce immigration law and maintain highway safety standards.

The DACA Argument Has Some Merit, But Still Doesn’t Work

The lawsuit argues that FMCSA’s concern about “unknown driving records” doesn’t apply to DACA recipients, who by definition arrived in the U.S. as children and have entirely domestic driving histories.

This is the strongest argument in the entire lawsuit, and it’s still not strong enough to prevail.

Here’s why:

First, DACA was created by executive action (2012), not by statute. It’s a prosecutorial discretion policy, the Department of Homeland Security’s decision to defer deportation for specific individuals. It was never intended to create an affirmative immigration status or authorize benefits beyond work authorization and deportation deferral.

Multiple federal courts have found DACA legally questionable. The Fifth Circuit found the program exceeded executive authority (though the Supreme Court ruled on narrower procedural grounds in DHS v. Regents). DACA exists in legal limbo, administratively renewable but statutorily unsupported.

Should federal agencies build permanent benefit programs (like CDL eligibility) on top of a temporary prosecutorial discretion policy that exists in legal limbo? That’s a policy judgment, and FMCSA reasonably concluded: no.

Second, DACA recipients are not lawfully present under immigration law. They are unlawfully present but protected from deportation. There’s a difference. Lawful presence is a specific legal status. DACA provides work authorization and protection from removal, but it does not provide lawful immigration status.

The original 2011 non-domiciled CDL rule was premised on the idea that lawful presence plus work authorization justified CDL eligibility. But if the premise is wrong, if EADs don’t actually prove lawful presence for all recipients, then the rule was legally defective from the start.

Third, even if we accept that DACA recipients have entirely domestic driving records, that doesn’t address the other concerns:

DACA status must be renewed every two years (currently extended to three in some cases)

Recipients remain in legal limbo with no path to permanent status under current law

CDL issuance based on DACA creates reliance interests that can’t be honored if DACA is ended

State DMVs lack the expertise to adjudicate which immigration statuses constitute “lawful presence”

The better policy: if you want to drive commercial vehicles in the United States, obtain lawful permanent resident status or U.S. citizenship. Work toward the green card application. Complete the immigration process. Then get your CDL.

For individuals like Mr. Rivera Lujan who’ve been here since age two, the answer isn’t “keep renewing your non-domiciled CDL indefinitely.” The answer is fix your immigration status. Apply for permanent residency. If there are legal barriers, work to address them. But don’t expect federal regulators to ignore statutory requirements because obtaining proper immigration status is difficult.

The Real Problem: Non-Domiciled CDLs Were Never Properly Authorized

The statute states that it issues CDLs to individuals “domiciled in the State.” The statutory exception for non-domiciled CDLs applies to:

Citizens of foreign countries with reciprocal licensing standards (Canada, Mexico)

Individuals domiciled in states with decertified CDL programs

That’s it.

The 2011 rule expanded non-domiciled CDL eligibility to foreign nationals temporarily present in the U.S. with work authorization. This expansion was never clearly authorized by statute; FMCSA relied on its general rulemaking authority under 49 U.S.C. 311.36 (motor carrier safety regulations) and 313.08 (CDL program standards).

But “motor carrier safety regulations” and “CDL program standards” don’t obviously include authority to override the statutory domicile requirement or create new categories of non-domiciled eligibility beyond those specified in statute.

If Congress wanted to authorize CDL issuance to asylum seekers, refugees, DACA recipients, and TPS holders, it could have amended 49 U.S.C. 313.11(a)(12)(B) to add those categories. They didn’t.

What FMCSA did in 2011 was administratively expand eligibility beyond statutory authorization. What they did in 2025 was correct the overreach by limiting non-domiciled CDLs to specific visa categories with strong federal vetting.

The lawsuit treats this as an arbitrary restriction. It’s actually a restoration of statutory fidelity.

The Court Should Deny the Stay

The DC Circuit has four factors to consider:

1. Likelihood of success on the merits The plaintiffs’ case is weak. FMCSA has substantial evidence of systemic state licensing failures, multiple fatal crashes demonstrating safety risks, and rational justifications for limiting non-domiciled CDL eligibility to visa categories with robust federal vetting. The good cause exception was properly invoked given the immediacy of the safety threat and the risk that advance notice would exacerbate the compliance crisis.

2. Irreparable harm to petitioners The plaintiffs claim irreparable harm from job losses and business closures. But this is economic harm, which courts generally find not irreparable because it can be remedied with money damages if the plaintiffs ultimately prevail.

The harm is caused by the plaintiffs’ own failure to obtain proper immigration status. Mr. Rivera Lujan has been in the U.S. since age two, he’s had decades to pursue permanent residency or citizenship. The Mercer Island worker has been employed 16 years, why hasn’t his green card application been processed?

These aren’t people being harmed by sudden regulatory changes. These are people whose temporary work authorizations were never intended to create permanent CDL eligibility, and who are now facing the consequences of building careers on a regulatory framework that exceeded statutory authority.

3. Harm to respondents if stay is granted If the court grants a stay, FMCSA’s rule is suspended. States resume issuing non-domiciled CDLs under the pre-September 29th framework. That means:

States with 25% error rates resume improper issuance

Drivers without verifiable safety records get CDLs

English language proficiency requirements remain inadequately enforced

More people die in preventable crashes

This isn’t speculative harm, it’s demonstrated harm based on five fatal crashes in eight months and systemic state licensing failures.

4. Public interest The public interest overwhelmingly favors FMCSA:

Highway safety requires properly vetted commercial drivers

Immigration law enforcement requires limiting benefits to lawfully present individuals

State licensing agencies need clear, enforceable standards

The traveling public deserves confidence that commercial drivers meet federal safety standards

The plaintiffs argue public interest favors preserving jobs and essential services. But the public interest in highway safety and immigration law enforcement outweighs the economic interests of individuals who hold CDLs based on work authorizations that don’t establish lawful presence.

What This Actually Means for Trucking

Despite all the legal drama, here’s the bottom line for the trucking industry:

The Good: This Helps the Market

Roughly 194,000 non-domiciled CDL holders will exit the industry over the next two years as licenses expire and can’t be renewed. That’s 5% of the 3.8 million active interstate CDL holders.

This is capacity reduction entering a market that desperately needs it. We’ve had three years of depressed freight rates, overcapacity, and carrier failures. Removing 5% of drivers will:

Tighten available capacity

Push freight rates upward

Improve earnings for owner-operators and small fleets

Reduce the devastating rate environment that’s pushed drivers into poverty wages

The trucking industry doesn’t need 200,000 more drivers working for unsustainable compensation. It needs a market equilibrium where rates support professional wages.

The Better: This Eliminates the “Driver Shortage” Lie

For years, industry advocates and large carriers have screamed about a “driver shortage” to justify:

Lobbying for lower age requirements (18-year-old interstate drivers)

Pushing for expanded visa programs

Resisting wage increases

Undermining safety regulations in the name of “efficiency”

There is no driver shortage. There’s a shortage of carriers willing to pay professional wages for qualified drivers.

If there were an actual shortage, freight rates would be through the roof. They’re not. They’ve been depressed for three years. Capacity is oversupplied, not undersupplied.

FMCSA’s rule eliminates one avenue that large carriers and public sector employers used to avoid paying competitive wages: bringing in foreign workers on temporary authorizations to fill positions that should go to Americans at professional compensation.

The Best: This Forces Proper Immigration Status

If you want to drive commercial vehicles in the United States professionally, get your immigration status right.

Apply for permanent residency. Complete the green card process. Become a U.S. citizen. Then get your CDL as a lawfully domiciled resident.

Don’t build a career on temporary work authorizations, prosecutorial discretion policies, and administrative expansions of regulatory authority that exceed statutory limits.

This rule forces that reckoning, and that’s good for everyone:

For American drivers, less competition from workers on temporary authorizations

For lawful permanent residents: clarity that proper immigration status matters

For prospective immigrants: clear incentive to complete the legal immigration process

For the industry: alignment between CDL eligibility and lawful permanent presence

FMCSA Got This Right

This lawsuit is a last-ditch effort by public-sector unions to preserve cheap-labor pipelines that never should have existed.

FMCSA found systemic failures in state CDL issuance. They found multiple fatal crashes involving drivers who either were improperly licensed or lacked verifiable safety histories. They found that states cannot properly implement the non-domiciled CDL framework.

So they fixed it, immediately, as the situation required.

Yes, some individuals will face economic hardship. Jorge Rivera Lujan and Aleksei Semenovskii are real people with real businesses who will lose their livelihoods. The Mercer Island municipal worker might lose his job after 16 years.

But their hardship doesn’t override:

The statutory requirement that CDLs be issued only to individuals domiciled in the issuing state

The government’s obligation to enforce immigration laws

The public’s right to expect that commercial drivers are properly vetted

The families of the 12 Americans who died in eight months in crashes involving non-domiciled CDL holders

AFSCME and AFT can file as many emergency motions as they want. The DC Circuit should deny the stay, let FMCSA’s rule stand, and allow states to fix their licensing programs properly.

And if Congress disagrees, if they believe asylum seekers, DACA recipients, and TPS holders should be eligible for commercial driver’s licenses, they can amend the statute to say so explicitly.

Until then, the FMCSA acted within its authority, responded appropriately to an emergent safety crisis, and did exactly what a regulatory agency should do when it discovers systemic failures that cause preventable deaths.

The lawsuit deserves to fail.