PART 1. THE ISSUE. 200,000 Illegal Immigrants Have CDLs and They're Killing People: The I-10 Crash Is Just the Latest.

California's AB60 Pipeline and Federal Immigration Failures Put Jashanpreet Singh Behind the Wheel of an 80,000-Pound Semi.

How you do one thing is often how you do everything. If you’ll break federal law to enter the country illegally, what do you have to lose? Our issue is that we are rewarding these people and creating programs that drive and encourage this behavior.

On Friday morning, standing in an orange jail jumpsuit before San Bernardino County Judge Shannon L. Faherty, 21-year-old Jashanpreet Singh heard three counts of gross vehicular manslaughter while intoxicated and one count of driving under the influence of drugs causing injury. He pled not-guilty.

Deputy Public Defender Zoe Korpi represents Singh. He remains held without bail at the West Valley Detention Center in Rancho Cucamonga. His next court appearance is scheduled for November 4.

Three people are dead because Singh, high on drugs, slammed a semi-truck into stopped traffic on California’s Interstate 10 at high speed without braking. Among the victims: Clarence Nelson, assistant basketball coach at Pomona High School’s Red Devils, and his wife, Lisa Nelson. The third victim, a 54-year-old man from Upland, has been identified to family but his name has not been publicly released.

So, how did an illegal immigrant who crossed the border just three years ago end up with a valid California commercial driver’s license, and a REAL ID at that?

On Tuesday morning, traffic on Interstate 10 near Ontario, California, came to a stop. Construction. Normal stuff. Cars and trucks slowed to a crawl, then came to a complete stop. Jashanpreet Singh Sandhu, driving a red Freightliner semi-truck registered to Mathaun Transport LLC out of Indianapolis, didn’t slow down. He didn’t brake. He didn’t swerve.

Dashcam footage from the truck captured the moment. The semi barreled into stopped traffic at full highway speed, slamming into the back of passenger vehicles with the full force of 80,000 pounds. (This is eerily similar ot the Danny Tiner, Mr. Bults Inc AZ TikTok crash. Tiner got 22 years in prison.)

The impact of the CA I-10 crash created an immediate fireball. Eight vehicles were involved in the chain-reaction pileup. Metal twisted. Glass shattered. Fuel ignited.

California Highway Patrol Officer Rodrigo Jimenez described the scene: “It was one of those crashes where there were car parts everywhere. We had a hazardous material incident. It was a very large scene. This could have been prevented if somebody had been paying attention sober.”

Singh wasn’t sober. CHP confirmed he was under the influence of drugs. Witnesses reported Singh never attempted to brake or avoid the collision. “It didn’t stop. It didn’t swerve. It didn’t make any kind of maneuvers,” one witness said. “It just went straight in.”

The Nelsons burned to death in their vehicle. The 54-year-old Upland man died in the flames. Four others were hospitalized with serious injuries. The scene stretched across multiple lanes, shut down the interstate for hours, and required hazmat crews to contain leaking fluids and extinguish fires.

While California officials make excuses, two families are planning funerals.

Clarence Nelson was an assistant basketball coach at Pomona High School, working with young athletes and helping shape their futures. Lisa Nelson was his wife. They were traveling westbound on the I-10 near Ontario when Singh’s truck failed to brake before impact.

According to Department of Motor Vehicles reports confirmed this week, Singh did have a valid commercial driver’s license to operate a semitruck. According to the California State Transportation Agency, Singh was issued “a federal work authorization until 2030,” and his commercial driver’s license is “a federal REAL ID, which he was ‘entitled to receive given the federal government’s confirmation of his legal status.’”

California gave a man who illegally crossed the border in March 2022, a man who was apprehended by Border Patrol and released under “alternatives to detention,” not just a CDL, but a REAL ID CDL, supposedly valid until 2030. This ISN’T THE FIRST OR ONLY ONE.

CA’s Governor, Gavin Newsome, argues, “The federal government approved and renewed this individual’s federal employment authorization multiple times, which allowed him to obtain a commercial driver’s license in accordance with federal law.”

Those are the only two options: either Singh committed fraud, or California DMV gave him a license knowing he had no legal status. There’s no third explanation that makes this acceptable.

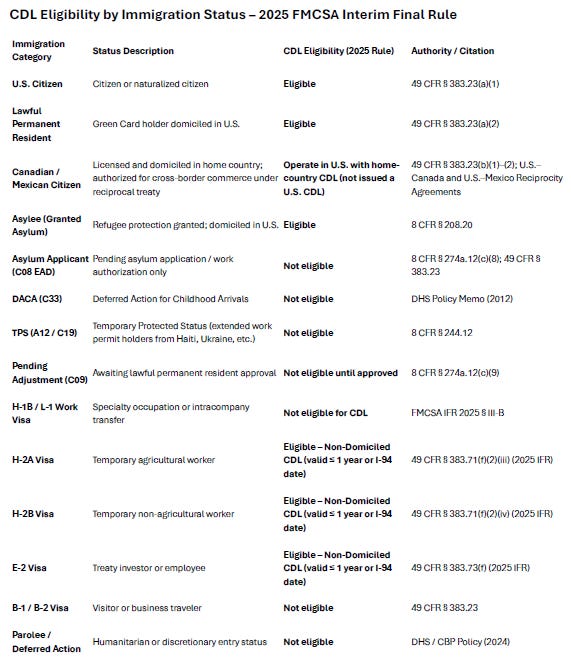

It is important to understand that work authorizations aren’t all created equal, and having one doesn’t necessarily mean you can get a CDL. My chart I put out since other immigrant-related crashes breaks this down on Substack with thirty other articles on how illegal trucking has taken over our highways.

Department of Homeland Security records confirm that Jashanpreet Singh Sandhu is an Indian national who illegally entered the United States through California’s El Centro Sector in March 2022. Border Patrol apprehended him. Then they released him under the Biden administration’s “alternatives to detention” policy while awaiting an immigration hearing.

That hearing never happened. For three years, Singh lived in Yuba City, California. At some point during those three years, he walked into a California DMV and obtained a commercial driver’s license, complete with REAL ID designation.

Following his arrest for Tuesday’s fatal crash, Immigration and Customs Enforcement lodged an immigration detainer on Singh. He’s now listed in detention records at Mesa Verde Detention Center in Bakersfield.

Breaking Down California’s AB60 Pipeline

Understanding how an illegal immigrant obtained authorization to drive a commercial vehicle requires understanding California’s multi-step licensing system, and where it failed at every single level. (You can find a deep breakdown of specific State and Federal programs that enable this craziness here.)

Step 1: The AB60 License

California Assembly Bill 60, passed in 2013 and effective January 1, 2015, allows undocumented immigrants to obtain a driver’s license without proof of legal presence in the United States. These “AB60 licenses” are marked “Federal Limits Apply” and cannot be used for federal identification purposes.

The stated purpose was to allow undocumented immigrants to drive legally, obtain insurance, and avoid deportation risks from traffic stops.

The actual effect was creating a pipeline for illegal immigrants to obtain Commercial Driver’s Licenses eventually.

AB60 explicitly prohibits its use for CDL issuance. According to California DMV regulations and federal law (49 CFR Part 383), applicants must provide a valid Social Security number to obtain a CDL.

But here’s the loophole: Once someone holds an AB60 license, they can apply for a Commercial Learner’s Permit (CLP).

Step 2: The Commercial Learner’s Permit

Under California DMV policy, anyone holding a valid California driver’s license, including an AB60 license, “may apply for a Commercial Learner’s Permit (CLP), but must have a CA driver’s license prior to getting a CLP.”

The CLP allows behind-the-wheel training on public roads when accompanied by a CDL holder with proper endorsements.

The regulatory gap is staggering. Federal regulations (49 CFR 383.25) require that CLP holders be “accompanied by the holder of a valid CDL who has the proper CDL group and endorsement(s).” But there’s no robust verification that the supervising driver is actually present, properly credentialed, or that the CLP holder has legal immigration status.

Step 3: The Full CDL, Where the System Completely Collapses

This is where the system supposedly has guardrails. Federal law requires verification of legal status for CDL issuance. Social Security numbers must be provided and verified.

So how did Singh get his CDL?

Several possibilities exist, and investigators are working to determine which one applies in this case:

Document fraud: Using fraudulent or stolen identity documents, including Social Security numbers belonging to other individuals. This is the most common pathway and involves sophisticated document mills that produce virtually indistinguishable fake birth certificates, Social Security cards, and work authorization documents.

System bypass: Exploiting gaps in DMV verification systems that fail to cross-check immigration databases in real-time. Many state DMV systems rely on employees manually entering data into federal verification systems, creating opportunities for errors or deliberate circumvention.

Alternative authorization claims: Claiming work authorization through Temporary Protected Status (TPS), Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA), Employment Authorization Documents (EADs), or other programs, despite not actually qualifying. The verification gap between claiming status and actually having it can be weeks or months, during which licenses get issued.

Out-of-state licensing: Obtaining a CDL in another state with looser verification requirements, then transferring or reciprocating it in California. States like Washington, Illinois, Minnesota, and New York have notoriously weak verification systems.

DMV corruption or negligence: Employees who fail to verify documents properly, skip required database checks, or are complicit in fraudulent applications. Multiple investigations have documented that DMV employees have accepted bribes to issue improper licenses.

California Highway Patrol and FMCSA investigators are determining exactly how Singh obtained his CDL. But regardless of the specific mechanism, one fact is undeniable: the system failed to prevent an illegal immigrant from receiving authorization to operate commercial vehicles, and three people are dead because of it.

Understanding Singh, Sandhu, and the Identity Verification Nightmare

The driver’s full name, Jashanpreet Singh, reflects Sikh naming conventions that create genuine challenges for background checks and identity verification, but also create opportunities for exploitation and fraud.

In Sikh culture, “Singh” (meaning “lion”) is a religious middle name adopted by baptized Sikh men. It’s not a family surname, it’s a religious title shared by millions of Sikh men regardless of family lineage. “Sandhu” is what I believe this driver’s actual family name is, based on ancestry records, but it has not been proven yet (known as a “got” in Punjabi, referring to clan or lineage).

Different documents list the name as Jashanpreet Singh Sandhu, Sandhu Jashanpreet Singh, Jashanpreet Singh, or Jashanpreet Sandhu. The truck displayed “SANDHU” markings on the windshield, but DOT records show registration to “Mathaun Transport LLC.”

This creates a nightmare for background checks. A single person appears in different databases under name variations, making it nearly impossible to connect criminal history, traffic violations, or immigration status without biometric verification.

This isn’t unique to this case. Millions of unrelated individuals share the name “Singh”. Family relationships cannot be determined solely from names. Western databases designed around unique family surnames fail catastrophically when applied to naming conventions from South Asia. I started doing genealogy as a child, looking for my mother and her family, and have since found lost family members around the world for many people, but naming conventions are a nightmare.

Mathaun Transport’s History

The truck Singh was driving was registered to Mathaun Transport LLC, a company with USDOT number 3099318 and MC number 76555. Its corporate history reveals the exact kind of red flags that should trigger immediate investigation, and the exact kind of entity that survives our broken enforcement system.

The Corporate Trail

July 31, 2024 , Mathaun Transport LLC files Articles of Organization with the Indiana Secretary of State.

Principal Office: 1402 N Commerce Ave Unit M, Indianapolis, IN 46201

Registered Agent: Harjit Singh

Single-member LLC

Service of process email: bksrulez@gmail.com (seriously)

FMCSA records show Mathaun Trans, LLC operates a brokerage using the same email, but in California from:

3723 Poppy Hill Way, Sacramento, CA 95834

Agent: Harjit Singh

Phone: (916) 692-8477

Email: mathauntransport@gmail.com

March 5, 2021, Earlier records list:

4050 Woodbridge Ave Apt D, Edison, NJ 08837

The company’s current FMCSA profile lists approximately 10 power units and 14 drivers engaged in interstate freight operations. The phone number on file is (732) 770-9725, a New Jersey area code, despite the Indianapolis registration.

Singh was living in Yuba City, California, approximately 40 miles north of Sacramento. The truck was operating in California, but the registered carrier is Indianapolis-based with a New Jersey phone number and a history of addresses stretching from coast to coast.

The Crash History

This wasn’t Mathaun Transport’s first crash. It wasn’t even their first serious crash in the last three months.

August 27, 2024, Ohio crash

Tow-away incident

California license plate ZP06295

August 3, 2024, California crash

2 injuries

Hazmat released

California license plate YP47556

October 22, 2025, California I-10 crash

3 fatalities (Coach Clarence Nelson, Lisa Nelson, 54-year-old Upland man)

4 injuries

Massive fireball

Eight-vehicle pileup

Three crashes. Two states. Multiple injuries. Hazmat release. And now three fatalities.

Why is a carrier with this record still operating? Because our enforcement system is broken. FMCSA’s Safety Measurement System takes time to update. Because state enforcement agencies are overwhelmed and underfunded. Because by the time a carrier’s safety score triggers intervention, they’ve already moved to a new DOT number, a new state registration, a new shell company.

The Non-Domiciled CDL Scandal Didn’t Start This Week

Dale Prax of Freight Validate and I have been talking about this for years. Singh’s case isn’t an isolated incident. It’s part of a massive, systemic failure in how states issue commercial driver’s licenses to non-citizens. This failure has put an estimated 200,000 unauthorized or questionably authorized drivers on American highways.

“Non-domiciled CDLs” were created for U.S. citizens living in jurisdictions that were stripped of the ability to issue CDLs (primarily military personnel stationed overseas and residents of U.S. territories). Over time, states twisted the program into a backdoor way to give foreign nationals, including many with questionable legal status, authorization to operate commercial vehicles.

Texas: 51,993 non-domiciled CDLs issued since 2015 (including renewals). Cross-border trade with Mexico, agricultural operations, and oil fields all depend heavily on these drivers.

Illinois: 13,668 non-domiciled CDLs issued since 2015.

In 2015: Just 80 issued (0.1% of total CDL issuances)

In 2025: 40% of all CDL issuances were non-domiciled

That’s not a typo. In Illinois, 40 percent of commercial driver’s licenses issued in 2025 went to non-domiciled applicants.

Washington State: 5,481 non-domiciled CDLs issued.

Share of first-time CDLs rose from 4% (pre-2020) to 16% (2024)

Minnesota: 3,350 non-domiciled CDLs issued since 2015.

Pre-2020: 1-2% of CDL issuances

2024: 8.7% of CDL issuances

California: State refuses to disclose non-domiciled CDL statistics despite multiple public records requests and federal inquiries. The California DMV’s stonewalling suggests the numbers are even worse than in other states.

New York, Pennsylvania, Ohio, New Jersey, Maryland: Combined have issued tens of thousands of non-domiciled CDLs with minimal verification of legal status or work authorization.

The Florida Lawsuit

In August 2025, Florida Attorney General Ashley Moody sued California and several other states for issuing CDLs to illegal immigrants, arguing that these licensing practices violated federal law and created interstate safety hazards.

The lawsuit highlighted California’s AB60 pipeline and documented how illegal immigrants were obtaining commercial licenses through fraudulent claims of work authorization, then operating trucks across state lines, including into Florida.

Florida’s argument was simple: If California wants to issue driver’s licenses to illegal immigrants for personal use within California, that’s California’s decision. But when those licenses authorize operation of 80,000-pound commercial vehicles in interstate commerce, every state has standing to challenge the practice.

The September 29, 2025 Emergency Rule

On September 29, 2025, less than a month before the I-10 crash killed three people, the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration published an emergency rule addressing non-domiciled CDLs.

The rule prohibited states from issuing new non-domiciled CDLs unless the applicant had specific work authorization: H-2A (agricultural workers), H-2B (temporary non-agricultural workers), or E-2 (treaty investors/traders).

The rule gave existing non-domiciled CDL holders until March 1, 2026, to either obtain proper work authorization or have their licenses revoked.

The rule was a step in the right direction. But it was too little, too late, and riddled with enforcement gaps.

It didn’t stop Singh from being on the road. He already had his license. Under the emergency rule, he would have had until March 2026 to prove work authorization.

It didn’t address document fraud. Nothing in the rule helped DMVs detect fake Social Security numbers, stolen identities, or fraudulent work authorization documents.

It didn’t mandate real-time database verification. States can still process CDL applications without immediately cross-checking federal immigration databases.

It didn’t create consequences for non-compliance. States that refuse to implement the rule face no penalties, no funding cuts, no federal intervention.

FMCSA Administrator Robin Hutcheson issued statements about “public safety” and “legal compliance,” but the rule had no teeth. California, Washington, Illinois, and other sanctuary states simply ignored it, confident that federal enforcement would never materialize.

Three weeks after FMCSA’s emergency rule, three people burned to death on Interstate 10.

State Sanctuary Policies

California’s AB60 license system is the most well-known pipeline for unauthorized drivers, but it’s not alone. Multiple states have implemented policies that prioritize illegal immigrant access to employment over public safety and federal law compliance.

California’s Multi-Layered Shield

AB60 (2013): Allows illegal immigrants to obtain standard driver’s licenses without proof of legal presence.

SB 54, the “California Values Act” (2017), limits state and local law enforcement cooperation with federal immigration authorities, preventing ICE notification when illegal immigrants are arrested.

AB 1747 (2018): Prohibits employers from allowing ICE workplace access without warrants, even when investigating employment of unauthorized workers.

Various sanctuary city ordinances: San Francisco, Los Angeles, Oakland, San Jose, Sacramento, and dozens of other cities have local policies further limiting cooperation with federal immigration enforcement.

The result is a state where illegal immigrants can obtain driver’s licenses, apply for commercial training, secure employment in transportation, and operate vehicles with minimal fear of immigration consequences, until they kill someone.

Washington State’s “Driving Equality” Disaster

Washington State implemented similar policies starting in 2019 with the “Driving Equality” bill, which allowed illegal immigrants to obtain standard driver’s licenses.

By 2024, Washington was issuing 16 percent of its CDLs as non-domiciled licenses, nearly triple the pre-2020 rate. The state’s sanctuary policies prevent state agencies from cooperating with ICE during traffic stops and DMV transactions.

Washington carriers now operate with significant percentages of drivers whose legal status is questionable at best, fraudulent at worst.

Illinois: From 80 to 40 Percent in Ten Years

Illinois represents the most dramatic example of how quickly non-domiciled CDL issuance can spiral out of control.

In 2015, Illinois issued just 80 non-domiciled CDLs, 0.1 percent of total CDL issuances. By 2025, that figure had exploded to 40 percent of all CDL issuances.

The Chicago area, with its massive distribution and logistics industry, has become a magnet for illegal immigrant truck drivers. Carriers operating out of Illinois warehouses and distribution centers routinely employ drivers with questionable legal status, confident that state enforcement is nonexistent and federal enforcement is sporadic at best.

Minnesota’s Ethnic Network Exploitation

Minnesota’s Somali and East African immigrant communities have created extensive trucking networks that often operate outside traditional regulatory oversight. While many are legal immigrants and naturalized citizens, the same ethnic networks have facilitated CDL access for those without proper status.

Minnesota issued 3,350 non-domiciled CDLs since 2015, with issuance rates jumping from 1-2 percent pre-2020 to 8.7 percent in 2024.

The state’s sanctuary policies and reluctance to enforce immigration status verification have made Minnesota another attractive state for illegal immigrants seeking commercial driving work.

The Punjabi Ethnic Economics Meets Immigration Enforcement Failure

Understanding the broader context of Singh’s case requires understanding the extensive Punjabi trucking networks that have developed across North America over the past two decades.

According to the Asian American Education Project, approximately 20 percent of the nation’s truck drivers are now Indian nationals, predominantly Sikhs from Punjab. The vast majority are legal residents or naturalized citizens. Many own successful trucking companies and operate professionally.

The rapid growth of these networks, combined with weak immigration verification, has created opportunities for illegal operators to infiltrate the industry.

Organizations like the North American Punjabi Trucking Association (NAPTA) have acknowledged concerns about hiring practices within their community that sometimes prioritize language ability and community connections over driving skills and legal status verification.

The ethnic network model works like this:

Step 1: An established trucking company or owner-operator, often a legal immigrant or naturalized citizen, sponsors or employs new drivers from their home region in Punjab.

Step 2: These new drivers, regardless of their legal status, gain access to commercial driver training through community connections.

Step 3: The new drivers obtain CDLs through the various pathways described earlier, AB60 pipeline, document fraud, out-of-state licensing, and DMV verification failures.

Step 4: They begin working for established carriers within the ethnic network, often paid in cash or through arrangements that avoid traditional employment verification.

Step 5: Eventually, some start their own companies, perpetuating the cycle.

This isn’t unique to Punjabi networks. Similar patterns exist in Hispanic, Eastern European, and Middle Eastern trucking networks. Any ethnic community with strong ties to specific industries develops these employment pipelines.

The problem isn’t ethnic networking itself, it’s when those networks facilitate employment of people without legal work authorization, and when government agencies refuse to enforce verification requirements because doing so might be characterized as “discriminatory.”

Stay tuned for PART 2. THE SOLUTION…