The Satisfactory Rating and the Border Zone.

Cross-border commerce has created a safety blind spot where carriers rack up violations without consequence and two border counties now rank at the 100th percentile nationally for safety events.

When I started digging through FMCSA enforcement data as a carrier who had just had an enforcement case decades ago, I was surprised to find carriers with more than one enforcement case. I expected to see the usual suspects: fly-by-night operations, chameleon carriers, the kind of companies that make experienced safety professionals roll their eyes, the one-off audit fail.

What I found instead was a maze of interconnected corporate entities, a trend of violations that refuses to improve, and questions that nobody at FMCSA seems to be asking.

VRP Transportes de Mexico S de RL de CV sits at the top of our enforcement analysis with 10 closed FMCSA enforcement cases and $50,540 in settlements since 2022. Every single case cites the same violation: 49 CFR 396.7(a), “Unsafe Operations Forbidden.” That’s the regulation that says you can’t operate a truck in a condition likely to cause an accident or breakdown.

Ten times. In three years. Same violation. $50,540 in fines paid.

Yet this carrier maintains a “Satisfactory” safety rating.

The Numbers Story

Between March 2022 and December 2025, VRP Transportes has racked up one of the most consistent violation records I’ve ever analyzed:

Overall Inspection Record:

6,734 total inspections

15,036 total violations (that’s 2.2 violations per inspection)

2,053 Out-of-Service violations

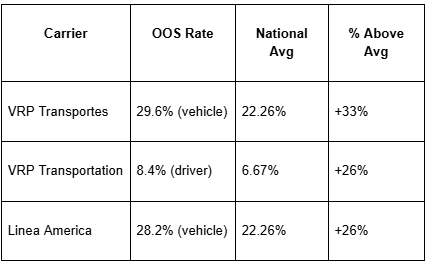

29.6% vehicle OOS rate (national average: 22.26%, VRP is 33% worse)

23.4% of inspections result in an out-of-service condition

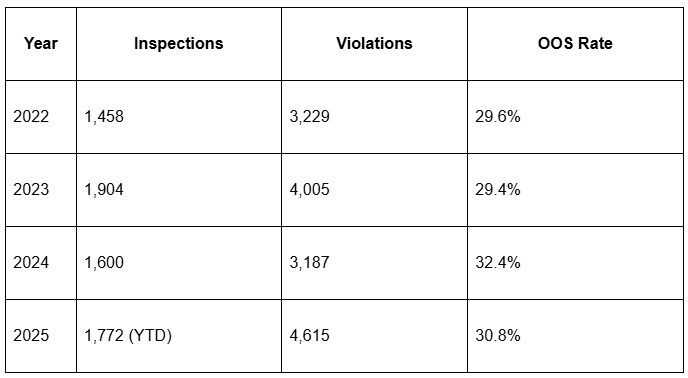

The Yearly Trend Shows No Improvement:

Notice something? The violation rate isn’t getting better. In fact, 2024 saw the highest OOS rate in the four years at 32.4%. That’s after years of enforcement cases and tens of thousands in fines.

What’s Actually Wrong With These Trucks?

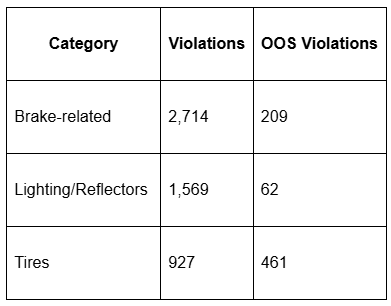

The violation breakdown reveals a carrier with systematic maintenance failures. Of the 6,836 violations in FMCSA’s BASICS data (24-month window):

97% are Vehicle Maintenance violations (6,622 total)

The top violation categories tell you everything you need to know:

The Most Common Specific Violations:

Inoperable Required Lamps, 408 violations

Underinflated/Leaking Tires, 363 violations (all 363 were OOS)

Brakes Out of Adjustment, 318 violations

Oil/Grease Leaks, 301 violations

Audible Air Brake Leaks, 250 violations

Defective ABS Indicator Lamps, 236 violations

Brake Valve Leaks, 235 violations

Missing Reflective Material, 219 violations

Wheel/Stud Issues, 206 violations

ABS Malfunction Lamps, 199 violations

When every tire violation results in an out-of-service order, and you have 363 of them in 24 months, that’s not random bad luck. That’s a maintenance program that doesn’t exist.

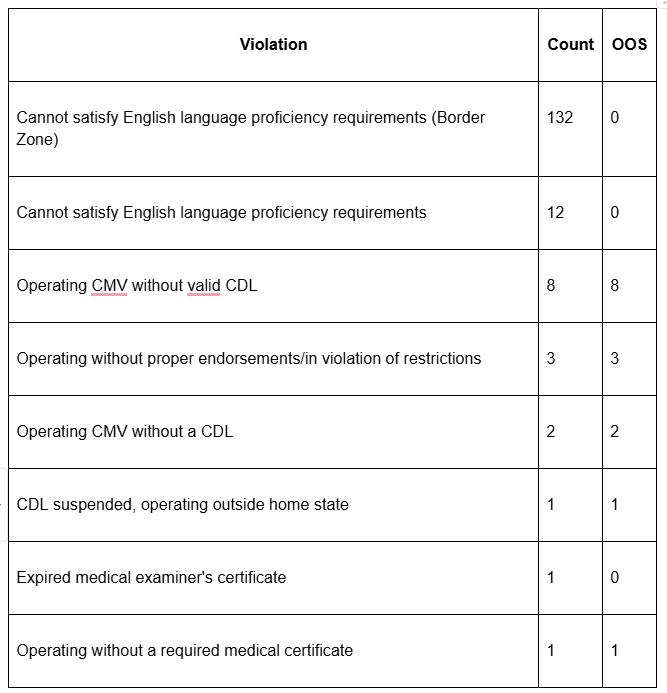

What’s Wrong With the Drivers?

The vehicle maintenance issues dominate the record, but the driver violations tell their own story. Over the whole inspection period, VRP drivers accumulated 305 driver violations resulting in 32 out-of-service orders.

The English-language proficiency violations are notable, 144 violations among drivers who cannot meet the requirement that CMV operators be able to read and speak English well enough to communicate with officials and understand highway signs. Under the border zone exemption, these don’t result in OOS orders, but they raise questions about training and qualification standards.

Eleven drivers were caught operating without a valid CDL or with improper endorsements. Every single one of those was placed out of service, because they literally weren’t qualified to be behind the wheel.

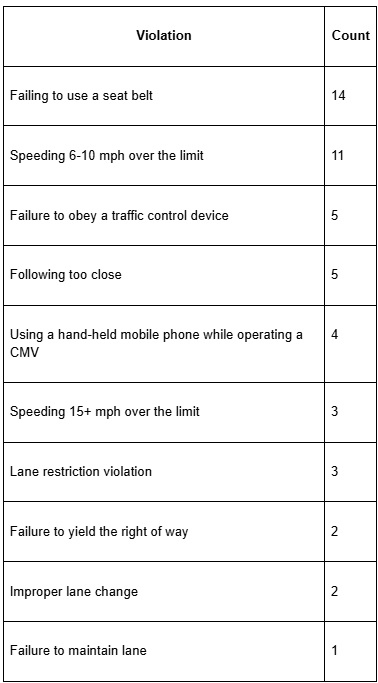

Unsafe Driving Violations (50 total, 0 OOS):

Speeding, phone use, following too closely, and running red lights are the violations that cause crashes. While none resulted in OOS orders (these typically don’t under current rules), they paint a picture of driver behavior that matches the maintenance culture: minimum standards, maximum risk.

Driver violations are lower volume than vehicle issues, but they follow the same trajectory. In 2025, driver violations spiked to 132, more than triple the 42 recorded in 2024. Either enforcement increased or driver quality decreased. Neither explanation is good.

The VRP Corporate Network

VRP Transportes doesn’t operate in isolation. According to carrier database records and FMCSA filings, the company is part of a network of interconnected carriers that share addresses and contact information:

THE PRIMARY OPERATION:

VRP Transportes de Mexico S de RL de CV (DOT 662058, MX-700803)

Physical: Blvd Oscar Flores Sanchez #10061, Juarez, CI 32695

Mailing: 9680 Plaza Circle, El Paso, TX 79927

Officers: Juan Orduno Coronel (Primary), Santiago Rodriguez (Secondary)

Fleet: 145 power units, 156 drivers

Founded: October 1996

Rating: Satisfactory (August 2016, yes, nine years ago)

THE CONNECTED CARRIERS:

VRP Transportation Inc (DOT 1882222, MC-678708)

Address: 9680 Plaza Circle, El Paso, TX 79927 (same mailing address)

Fleet: 46 power units, 46 drivers

Rating: Satisfactory (August 2023)

Founded: 2008

Driver OOS rate: 8.4% (national avg: 6.67%, 26% above average)

Linea America Transporte S de RL de CV (DOT 3240043, MX-1018445)

Physical: Blvd Oscar Flores 9905, Juarez (same street, different building)

Mailing: 9680 Plaza Circle, El Paso, TX 79927 (same address)

Fleet: 61 power units, 56 drivers

Vehicle OOS rate: 28.2% (26% above national average)

No safety rating; Last review: October 2022. “Non-Ratable”

VRP Towing Crane and Machinery Corporation

Shares contact information with VRP Transportation Inc

Limited public records available

CarrierSource explicitly flags that VRP Transportation Inc “shares contact information with the following carriers: Vrp Transportes De Mexico S De Rl De Cv, Vrp Towing Crane And Machinery Corporation, Linea America Transporte S De Rl De Cv.”

Same addresses. Same street. Same mailing location. There are actually more connections than this using Corporate Officer data and a corporate office location filing for Texas.

All Connected Carriers Exceed National OOS Averages:

When every connected carrier in your network runs above national averages, that’s culture.

The 1033 Humble Place Connection

The VRP network has another node: 1033 Humble Pl, El Paso, TX 79915.

According to Texas Secretary of State records, Victor Reyes Perez is listed as a Director at this address. The name that VRP appears to represent (27.6% of inspections list “Victor Reyes Perez” as the carrier name rather than the corporate entity).

Who’s Using This Carrier?

VRP Transportes hauls for major manufacturers in the maquiladora corridor. Based on shipper data from inspections:

Top Shippers:

PCE Technology / PCE Technology de Juarez, 432+ shipments

Vitesco Technologies, 185 shipments

Continental Automotive Systems, 126 shipments

TED de Mexico, 117 shipments

ECMMS, 94 shipments

Grupo American Industries, 40 shipments

Leggett and Platt, HP Inc., Expeditors International, various

These are legitimate multinational companies that have carrier vetting programs. They presumably check safety ratings. They presumably see “Satisfactory.”

What they don’t see is the 10 enforcement cases. The 15,000 violations. The 29.6% OOS rate. The network of connected carriers is all running above national averages. FMCSA’s rating system doesn’t show them all of that unless they’re really prepared to dig and find it.

The Enforcement Cases

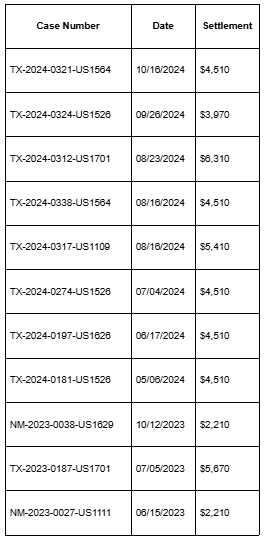

All 10 enforcement cases cite 49 CFR 396.7(a) , “Unsafe Operations Forbidden”:

Total: $50,540 in settlements

Note that two of these cases were filed under “Victor Reyes Perez” rather than the corporate name, another indicator of how the operation alternates between personal and corporate identities. Look at the pattern: Eight enforcement cases in 2024 alone. That’s one enforcement action every six weeks. At what point does the pattern itself become the story?

The Rating

The part that should concern every shipper, broker, and safety professional reading this is VRP Transportes de Mexico’s “Satisfactory” safety rating was assigned in August 2016.

That rating is nine years old.

Since that rating was assigned:

10 enforcement cases

$50,540 in fines

15,000+ violations

A vehicle OOS rate consistently 30%+ above the national average

The most recent compliance review? June 2023 marked “Non-Ratable.”

Non-Ratable means FMCSA conducted some form of review, but couldn’t or wouldn’t assign a new rating. The carrier keeps the old “Satisfactory” rating by default.

This is how the system works: Once you receive a Satisfactory rating, you keep it forever unless the FMCSA explicitly downgrades you. The violations pile up. The enforcement cases pile up. The fines pile up. The rating stays the same.

Brokers and shippers checking SAFER see “Satisfactory” and check the box. They don’t know the decade of deterioration behind it.

The Border Zone Crisis

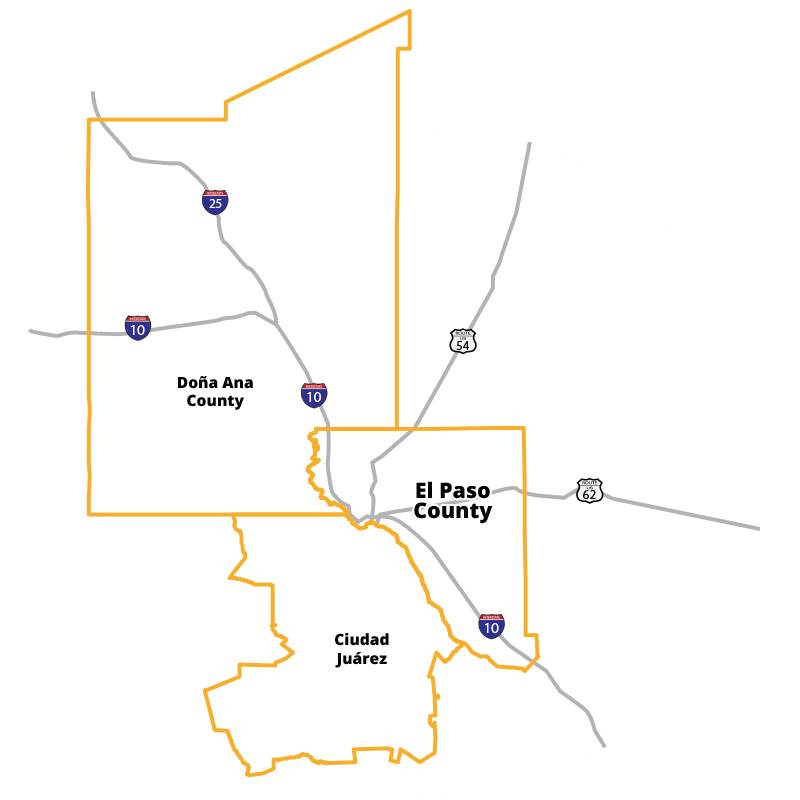

VRP Transportes isn’t an outlier. It’s a symptom. The El Paso-Santa Teresa corridor, where VRP operates, has become ground zero for unsafe commercial vehicle operations in the United States. The numbers are staggering:

El Paso County, Texas:

39,350 safety events, 100th percentile nationally

279 serious safety events, 96.5th percentile

Combined rating: HIGH-HIGH

Doña Ana County, New Mexico (Santa Teresa Port of Entry):

18,579 safety events, 100th percentile nationally

29 serious safety events, 97th percentile

Combined rating: HIGH-HIGH

That’s 57,929 safety events in two counties along a 50-mile stretch of border. Both counties rank in the 100th percentile for safety event volume. This isn’t a high-traffic adjustment. This is a crisis.

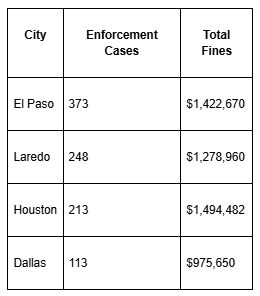

El Paso Leads Texas in Enforcement Cases

El Paso, with a metro population of 870,000, has more enforcement cases than Houston (7 million metro) and Dallas (7.6 million metro) combined.

The 396.7(a) Epidemic

Of El Paso’s 390 enforcement cases, 289 (74%) cite 49 CFR 396.7(a), “Unsafe Operations Forbidden.” That one violation code accounts for nearly $1 million in fines in this corridor alone.

The trend is accelerating:

2021: 12 cases

2022: 44 cases

2023: 87 cases

2024: 146 cases

That’s a 12x increase in four years.

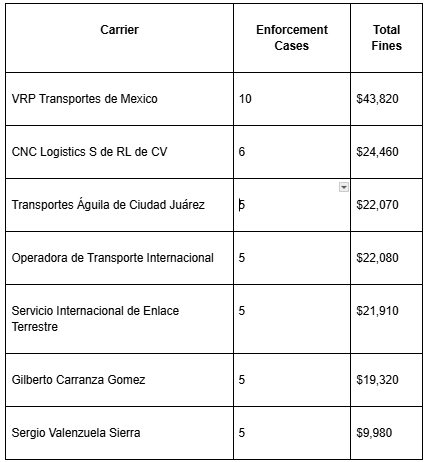

The Repeat Offenders

VRP isn’t alone at the top of the enforcement list. The El Paso corridor has produced a network of carriers with multiple enforcement cases:

Note that a separate entity, Victor Reyes Perez (the apparent namesake of VRP), also has three personal enforcement cases totaling $11,230, in addition to the 10 cases under the corporate name.

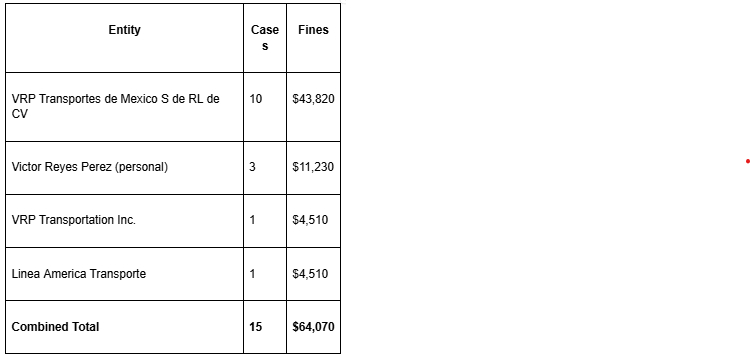

The VRP Network’s Full Enforcement Record

When you combine all connected VRP entities, the picture gets worse:

Fifteen enforcement cases across four connected entities. All operating from the same addresses. All with the same violation patterns.

The Border Zone Exemption

Many carriers operating in this corridor do so under FMCSA’s Commercial Zone exemptions, a regulatory framework with roots stretching back over four decades that has created what critics call a “safety blind spot” along the southern border.

Before 1982, Mexican trucks could travel anywhere in the United States without restriction. That changed with the Bus Regulatory Reform Act of 1982, when Congress imposed a moratorium confining Mexican carriers to narrow “commercial zones”, typically extending just 3 to 25 miles past border municipalities. The Motor Carrier Safety Act of 1984 formalized these boundaries as defined by the Interstate Commerce Commission.

NAFTA was supposed to change everything. When the agreement was signed in 1992, the U.S. and Mexico agreed to full cross-border trucking access, with Mexican carriers to have access to U.S. border states by December 1995 and to the entire country by January 2000. It never happened. President Clinton delayed implementation in 1995, citing safety concerns about Mexican trucks. A NAFTA arbitration panel ruled in 2001 that the blanket U.S. ban violated the agreement, but allowed the U.S. to impose safety requirements on individual carriers.

The result is a regulatory patchwork that persists to this day. While the FMCSA launched a Long-Haul Program in 2015, allowing select Mexican carriers to operate beyond commercial zones after rigorous vetting, the vast majority of cross-border traffic still operates under commercial zone authority, with reduced oversight.

The English Language Proficiency requirement illustrates how this plays out in practice. Under 49 CFR 391.11(b)(2), commercial drivers must “read and speak the English language sufficiently to converse with the general public, to understand highway traffic signs and signals, to respond to official inquiries, and to make entries on reports and records.” From 2005 to 2015, drivers who couldn’t demonstrate proficiency were placed out of service.

Then, enforcement essentially stopped. In 2015, CVSA removed English proficiency from its out-of-service criteria. In 2016, FMCSA issued guidance instructing inspectors to cite violations but not remove drivers from service. For nearly a decade, the regulation existed on paper but wasn’t meaningfully enforced.

President Trump’s April 2025 Executive Order restored out-of-service penalties for English proficiency violations, but with a critical exception. Under the FMCSA’s May 2025 enforcement guidance, drivers operating in border commercial zones remain exempt from out-of-service orders. Inspectors can cite them for violations, but cannot take them off the road or initiate disqualification proceedings.

This explains VRP’s driver-violation pattern: 144 English-language proficiency violations, zero out-of-service orders. Every single one was coded as a “Border Zone” violation, noted in the record, but with no enforcement consequences. Drivers who cannot communicate with inspectors, read highway signs, or respond to official inquiries continue operating because the commercial zone exemption shields them from meaningful enforcement.

The commercial zone framework was designed in the 1980s to facilitate cross-border commerce while the U.S. and Mexico worked toward full integration. Forty years later, that integration never happened. Still, the reduced oversight remains, concentrated in corridors like El Paso and Santa Teresa, where safety event data is now at the 100th percentile nationally.

Questions for FMCSA

Why does a carrier with 10 closed enforcement cases, the most in the nation, maintain a nine-year-old “Satisfactory” rating?

Has the agency investigated whether VRP Transportes, VRP Transportation, Linea America Transporte, and VRP Towing operate as a coordinated network?

When a carrier’s violation rate shows no improvement over four years despite repeated enforcement actions, what additional tools does FMCSA employ?

What explains the 12x increase in 396.7(a) enforcement cases in El Paso between 2021 and 2024?

Are Commercial Zone exemptions creating a regulatory blind spot that allows unsafe carriers to operate with reduced oversight?

Given that El Paso and Doña Ana counties are both at the 100th percentile for safety events, what enhanced enforcement resources have been deployed along the corridor?

What This Means for the Industry

This is a case study in systemic regulatory failure, and it’s not alone.

The El Paso-Santa Teresa corridor has become a concentration point for unsafe commercial vehicle operations. Two counties are at the 100th percentile nationally. 396.7(a) cases up 12x in four years. A network of carriers with multiple enforcement cases is still operating under “Satisfactory” ratings or no ratings at all.

The system is working exactly as designed: Assign a rating once, make it nearly impossible to change, exempt border operations from complete oversight, and let carriers with the worst enforcement records in the country continue operating.

Every broker running a carrier vetting check sees that green light. Every shipper’s compliance department sees “Satisfactory.” Every contract gets signed.

Until we make everyone with a part in the transportation financial chain, (shippers, consignees, carriers, and brokers) part of the liability chain, (think exposure) nothing will truly change the public safety environment.

Holy shit this is nuts, more disasters waiting to happen.